Julie Meridian

Photography by Joerg Metzner

Julie Meridian is a self-taught photographer in Evanston, Illinois, with a background in fine art and art education. Her curiosity for the “commonplace wonders” of the world—and her terrific eye for capturing beauty in objects the rest of us might find mundane—have inspired and influenced Martin and Shea’s design aesthetic. Often, Meridian’s techniques involve improvisation, dependent on the shifting daylight as it changes the appearance of say, an oak leaf. “My intent is to convey the mysteries that I feel in their presence,” she says. We chatted with her about art, inspiration, and the benefits of limiting yourself.

Why are you drawn to photography?

I have worked in a lot of different media, but I was seduced by a camera’s ability to capture the quality of light and shadow, which speaks to my own themes of transience. The camera is a tool I use to express a personal artistic vision.

What do you mean?

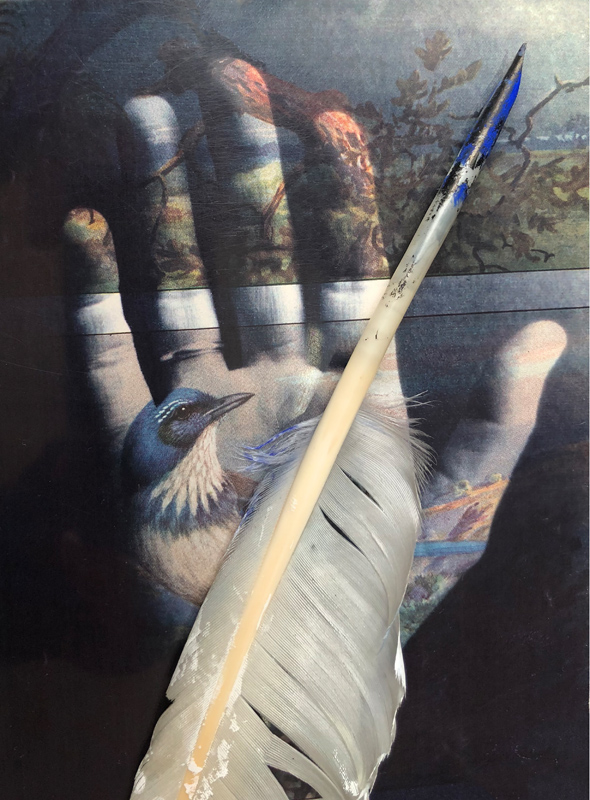

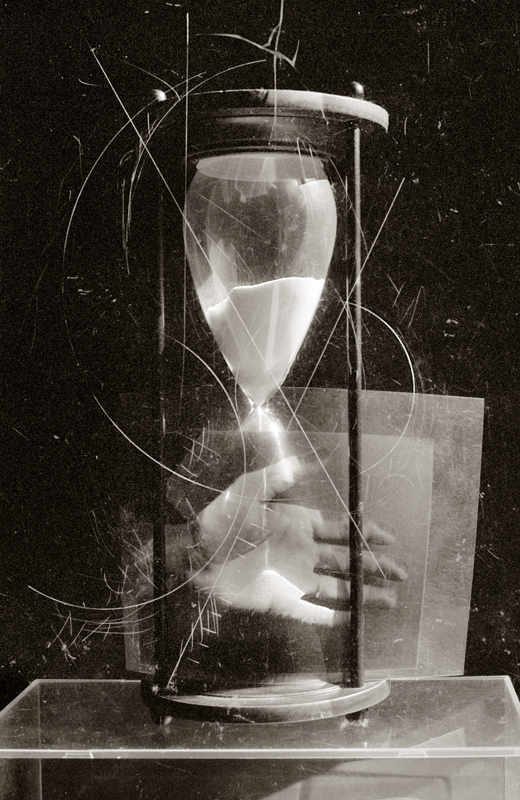

When I look closely at ordinary things that often go unlooked—leaves, seed pods, feathers and sticks and shells—it provokes a feeling of curiosity and wonder. My themes have a lot to do with the ephemeral nature of life. But also life tenacity. So many things in nature exist only for a brief time and then they die. It’s a reminder of my own lifespan but also a sense of some kind of transcendence and beauty.

How and why do you use Plexiglas in your art?

Sometimes I place Plexiglas, glass, acetate, and clear Lucite blocks between the camera and the subject to reflect something from the environment into the image. It’s a way of layering images that I capture in the camera, which speaks to the way we see things. We always see through the lens of our own personal vision, reminded of things from our memory, imagination, and triggered emotion. It’s never just the little thing in front of me.

What project are you excited about at the moment?

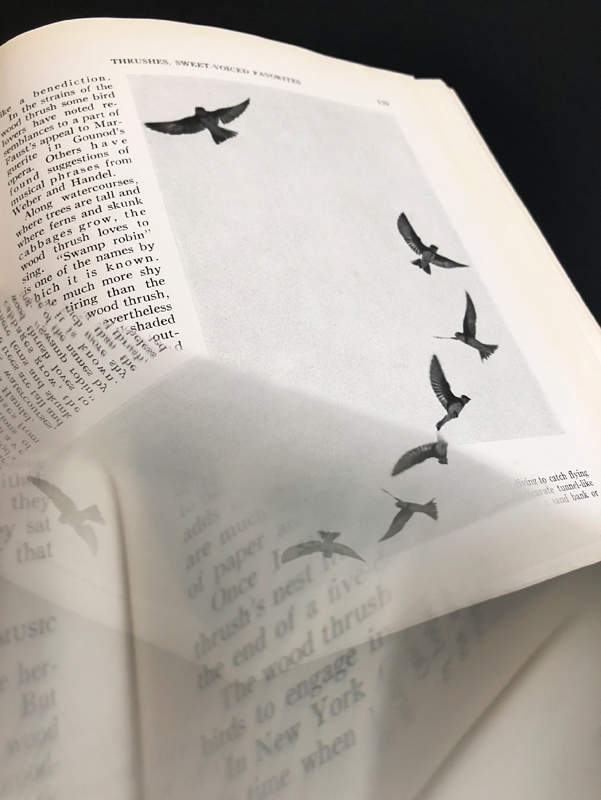

In my latest series, The Book of Birds: An Artist’s Requiem, I’m inspired by a particular book, and created my own version of the book. It’s the Book of Birds and was published in 1932.

What makes it so fascinating to you?

I was drawn to the illustrations and the text, which was lyrical and personal. And the poignancy . . . the fact that many of the birds are now extinct. The ivory-billed woodpecker is in the book, and it went extinct in the 1950s. I’ll never be able to hear that bird. My grandchildren will not. I’m trying to photograph what only exists in my imagination. I’m interested in creating invented images, not just documentation. I wanted some images that seemed to suggest that birds were flying off the page completely.

How do you define a good photograph?

An element of mystery exists in the image. Something that is nonverbal and not just immediately clear. It doesn’t necessarily mean obscure. To be able to see something in a way that you haven’t seen before. I’m looking for the questions, not the answers. I haven’t found the answers. But I’m getting better at asking the questions.

You speak of “limiting” yourself. What does that mean?

I limit myself by using simple objects, natural light, and an iPhone as a camera. The world is too much. I can’t say it any better. I would rather know a small part of the world in an intimate way. We can all make our contributions.

How does living in the Midwest inspire you?

Evanston has a lively art community. I find that stimulating. I will say that even though I traveled some and I’m intrigued by what I find elsewhere, my home is the Midwest. I’m drawn to the Midwest, oak trees and maple trees. Not palm trees. l love walking along the lake, seeing the changes of color palette on the sky and water depending on time of day and weather.

What’s the best advice you ever heard?

Michelangelo told a student, “Draw Antonio, draw Antonio, draw and don’t waste time.” Inspiration doesn’t just come out of the blue. It’s from those small things from our collections that our work usually evolves. I just start experimenting. The more I practice, the more fluid I feel with my tools and techniques. And it’s a two-way process: those tools and techniques inform and shape me, even as I am learning to refine and direct them.

What’s your hope for when a stranger looks at your art?

I hope that my images invite people to linger for a while, to look and spend some time with the image and see something they hadn’t noticed with first glance. Maybe trigger some musing of their own, or feel some connection to the transience we all feel. Or encourage other people to look more closely to see some of the wonder that I see in these things.

Like everyone else, I’m adjusting to the quick turn of events. But there is so much beauty in the world. For someone like me who can spend hours staring at a dead oak leaf, it’s not hard. Every day is filled with stories. I could live 100 years and not tell even a fraction.